Bruno Schulz, the great Jewish, Polish and Ukrainian Modernist writer, has become a cult favorite in the decades after he was murdered by a Nazi officer. Last month, the Bruno Schulz Festival was held in Drohobych. The Ukrainian-American political consultant and bibliophile Peter Zalmayev travelled to the festival to present his privately commissioned and published edition of a Schulz story. Zalmayev explains the appeal that the great writer continues to hold seven decades later and the continued influence he plays on world literature.

I first learned about the enigmatic Bruno Schulz when I read David Grossman’s article “The Age of Genius” in the June 2009 issue of The New Yorker magazine. The epiphany that I subsequently experienced when I picked up Schulz’s stories closely resembles Grossman’s own: “You open a book by an author you don’t know, and suddenly you feel yourself passing through a magnetic field that sends you in a new direction, setting off eddies that you’d barely sensed before and could not name.”

Grossman transformed his love for Schulz ‘the creator’ into a yearning to save Schulz ‘the man’, attempting with this one gnomic impulse to retrospectively right one of the Holocaust’s greatest crimes against art. In Grossman’s great novel, “See Under: Love,” Schulz is allowed to flee the Nazi-occupied Drohobych by turning into a salmon and swimming away, to safety.

Soon after undergoing a similar experience, I devoted myself to reading (and soon enough beginning to collect) everything connected with Schulz. I swept through the rapidly ballooning body of scholarly “Schulzology” as well as the reviews of his works and all of the secondary novels inspired by him and that featured him as a character. I quickly realized that I was in illustrious company with my Schulzian fixation. His many enthusiastic champions have included literary titans such as Philip Roth, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Cynthia Ozick, John Updike, Salman Rushdie and Danilo Kiš. Discovering Schulz was, indeed, akin to “passing through a magnetic field” – a sort of initiation ceremony granting entry into an exclusive club – nay, a devoted literary cult.

I began building my own private “Museum of Schulz,” by collecting every edition of his stories in every translation that had ever been published. To this I added books about Schulz as well as catalogs and posters from exhibits of his graphic oeuvre. My total collection currently stands at more than 200 items.

Last summer, I was finally able to find the time to embark on my long awaited pilgrimage to Drohobych, and into the heart of Schulz’s hermetic universe and muse. Roaming the streets and parks of this remarkably well-preserved town, I felt like pinching myself – so strong was the illusion of having stepped into Schulz’s pages that I felt as if I was about to bump into Eddie, hobbling along on his crutches, or catch sight of the demented Tluya, digging through her motley rags in the bushes. These are just 2 of the ghosts of the characters that populate the dreamscape of Schulz’s world.

Schulz published his first collection of stories, “Cinnamon Shops,” in 1934, without universal acclaim, but with recognition by Poland’s most sophisticated literary circles. Major literary figures such as Zofia Nałkowska and Witold Gombrowicz immediately identified Schulz’s rare talent and grew to appreciate him as an artist and as a man, if not always partaking in his idiosyncratic artistic aesthetic. The second collection of stories, “Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass” followed three years later. It cemented Schulz’s status as a rising star in the firmament of Polish letters.

The writer’s life was to be cut tragically short five years later, in 1942, by a Gestapo officer’s bullet on a Drohobych side street. Despite the strenuous efforts of his Polish friends and benefactors to smuggle Schulz out of the Nazi-occupied city, the artist hesitated to take the plunge. Instead, he bided his time and secured a temporary lease on life by contracting himself to paint frescos on the wall of the bedroom of Nazi officer’s child. The lease on life expired when the artist ventured out onto the streets on a “black Thursday,” clutching a loaf of bread, the same day that the Nazis decided to stage a “prophylactic” orgy of killing the city’s Jews.

With the death of Schulz ‘the man’, the life, the myth and the mystery of Schulz the artist was born. As the preeminent Ukrainian writer and translator Yurii Andrukhovych – the translator of the most recent Ukrainian edition of Schulz’s stories – puts it “Schulz has become the object of his own mythologizing, the subject of several myths: Schulz has not died, he is still hiding from the Gestapo; Schulz has received the Nobel prize, but doesn’t know about it; Schulz is still writing his novel ‘Messiah’ – but now, underground.”

The “Messiah” was the novel that Schulz had been working on for several years before his demise, and whose manuscript he entrusted for safe-keeping to an unidentified friend. The “Messiah” became the holy grail for the prominent Polish poet Jerzy Ficowski, who eventually became Schulz’s canonical biographer. Ficowski died, having spent decades unsuccessfully looking for the lost masterpiece (and I don’t doubt that it was, indeed, a masterpiece), but not before serendipitously leading a team of German film-makers in 2001 to the discovery of Schulz’s frescos in the villa taken over by the Nazi officer.

The sensational discovery of the frescoes and their equally sensational and shocking subsequent removal and transportation to Israel by operatives of the Yad Vashem museum is a topic worthy of a separate book. Suffice it to say, it only contributed to the myth of the author and his “Messiah.” Schulz has, indeed, become a literary “Messiah” for scores of famous writers, incarnating in the pages of their novels as the purported father of a Swedish book critic in Cynthia Ozick’s “The Messiah of Stockholm”, as a martyred Jewish writer in Philip Roth’s “The Prague Orgy”, the aforementioned salmon of David Grossman’s “See Under: Love,”, the friend of the protagonist in Nicole Kraus’s “The History of Love,” and the Schulz of Maxim Biller’s recent novella, “Inside the Head of Bruno Schulz,” where Schulz feverishly composes a letter to Thomas Mann, imagining having sighted the latter on the streets of Drohobych.

The nooks and crannies of Schulz’s “Street of Crocodiles” became the nooks and crannies of the Andalusian town in Salman Rushdie’s “The Moor’s Last Sigh.” A worm-hole leading into Drohobych’s parallel dimension was found when Jonathan Safran Foer die-cut into Schulz’z “Street of Crocodiles,” to discover his own appropriated work “Tree of Codes.” “The letters that were before beetles had turned into eyes, into the eyes of Bruno Schulz, and they were opening and closing again and again, some eyes clear like the sky, shining like the sea’s spine, which was opening and blinking, again and again, in the middle of total darkness,” comments the protagonist of Roberto Bolaño’s novel “Distant Star,” while reading Schulz’s story.

Finally, in the field of visual arts, two interpretations of Schulz’s oeuvre among many deserve to be mentioned here: “The Street of Crocodiles,” a stop-motion animation by the iconic Brothers Quay and “The Hourglass Sanatorium” by Wojciech Has, which went on to win the Jury Prize at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival.

Just like his native town, Bruno Schulz and his work are located at the crossroads of Polish, Jewish and Ukrainian cultures, embodying and detached from them all in their interiority and universality and not fully belonging in either. While Schulz’s importance to Polish literature is now recognized to roughly the same degree as Chekhov is to Russian, and while Israel esteemed him a prominent enough part of the Jewish cultural heritage to have warranted a commando-style fresco-cutting operation (the so-called “Schulz-gate”), Ukraine’s path to embracing the artist has been long and complex. The first Ukrainian translations of Schulz’s stories began appearing in the early 1990’s, and at least three different translations in various editions appeared during the following two decades. Yurii Andrukhovych published what some say is the definitive Ukrainian translation of Schulz’s complete stories in a beautiful edition by the “A-BA-BA-GA-LA-MA-GA” publishing house in 2013.

Since 2004, Drohobych has hosted the biennial International Bruno Schulz Festival, organized jointly by the Bruno Schulz Festival Society in Lublin and the Drohobych Pedagogical Institute’s Polish Studies Center. I had wanted to attend the Festival ever since my discovery of Schulz in 2006 but one thing or another has prevented me from making the trip. Then, in April 2015, the chain of encounters that eventually led me to the Festival was forged as I was wandering the vaulted space of the Arsenal International Book Festival in Kiev. I came upon a young lady sitting modestly in a small makeshift booth, exhibiting her book illustrations. The wrenching expressiveness of Katya Slonova’s figures reminded me of the work of Egon Schiele. If the “aliveness” of her characters brought to mind those drawn by Schulz, there was a good reason for it, as I soon discovered: Slonova, likewise, had been infected by the sting of the Schulz bug and was a devoted lover of his literary and visual wizardry.

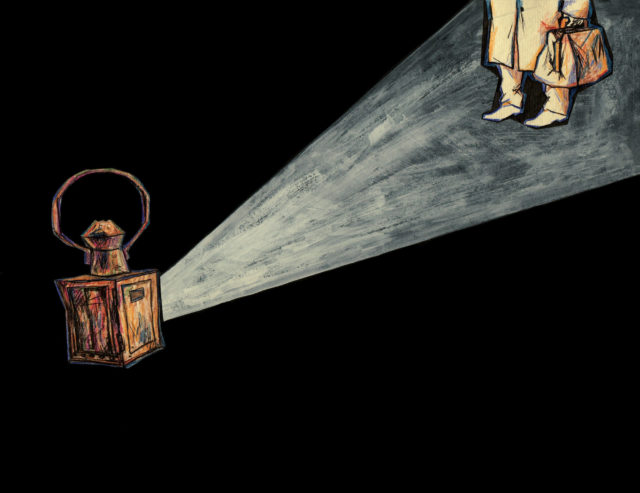

I stayed in close contact with Slonova until the next year’s Arsenal, buying a few of her illustrations and commissioning a portrait of Schulz for my collection. Eventually, the idea came to me to publish a new visual interpretation of Schulz work – he himself being an accomplished illustrator of his own stories – with Slonova as the visual interpreter. The decision to choose the “Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass” story for publication in the illustrated edition came easily. Simply put, even in the context of Schulz’s unique body of work, this story looms as one of the most dreamlike, heart-rending if also sinister pieces of writing in the history of literature. As this project’s sole function is that of an homage to a beloved writer, it was decided to publish it in the creator’s original Polish.

And what better excuse to finally make it to this year’s Bruno Schulz Festival than to present the book there? The book was published by the Meridian Chernowitz publishing house shortly before the Festival as a limited, numbered and signed edition that came in a special slipcase. Slonova and I were honored to have the opportunity to present the book at this gathering of Schulz lovers, which took place on June 3-9, 2016. Among them were the leading scholars of Polish literature, practitioners of the emerging ‘Schulzology’ studies, acclaimed Ukrainian writers such as Yurii Andrukhovych and Serhiy Zhadan, the Polish Ambassador to Ukraine and celebrated figures such as Adam Michnik, Poland’s leading intellectual and a father of Solidarność.

From its modest beginnings in 2004, the Schulz Festival has gradually gathered steam, drawing major cultural celebrities from Poland, Ukraine, Israel, the US, attracting ever-bigger crowds of visitors. This year, the Festival has reached its pinnacle, going far beyond the format of the academic symposium to include cultural performances, art installations, an exhibit in Drohobych’s synagogue, and concerts by the aforementioned writers, Andrukhovych and Zhadan. In a much-welcome display of the city’s willingness to finally go beyond the narrow partisanship of the Ivan Franko (a major Ukrainian classic writer likewise hailing from Drohobych) and Bruno Schulz divide and to accept Schulz on equal terms, the mayor’s deputy greeted the participants at the opening session.

As David Goldfarb, a prominent scholar of Polish literature tells us in the introduction that he kindly supplied for our edition, “Ekaterina Slonova gives us an image of Schulz’s world of light figures on a dark ground, illuminating an aspect of Schulz’s “Sanatorium” that is perhaps not present in Schulz’s own graphic works as we perceive them… Slonova’s new illustrations expose a visual layer of Schulz’s imagination that Schulz kept to himself, buried within his artistic process, and as such, these new images cast light on a stratum of the narrative that we as readers may have also neglected.”

And so, Bruno Schulz lives on, in all his myriad incarnations, and it has been my great pleasure and honor, with this project, to have accompanied the great artist for a short stretch of his endless journey.

Peter Zalmayev is the director of the Eurasia Democracy Initiative, a board member of the American Jewish Committee, and International Outreach Coordinator for the Babyn Yyamar Project, Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter

Origin – odessareview.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.